Bernard Langlais, 1921–1977

Bernard Langlais’s first studio was in the loft of his grandparents’ barn. Beneath the rafters, he copied pictures from magazines, drew comic strips, and became confident that he wanted to be an artist. Referring to this rustic, art-filled space, his wife Helen said, “In a way, he spent the rest of his life recreating it.”

Langlais was fiercely intuitive, charmingly quick-witted, and a restless homebody. He produced more than a full life’s work in his fifty-six years: art in staggering quantities and often immense proportions. He moved from commercial design to painting to wood relief then sculpture, fervently seeking an ever-more satisfying physical relationship to the things he made. Constant experimentation, recycling, and maximizing materials were principles of his art. Most of his late works depict animals, a subject he found visually rich but also morally compelling. He admired animals’ instinct to care for themselves and their fellow creatures.

In Cushing, Maine, where Langlais spent his final decade, he constructed a dynamic art environment on the land around his house and tended to it in the spirit of a farmer or homesteader. On cold winter days, he retreated to a drawing table in the loft of his barn, set against a bank of windows. He sketched birds, bears, giraffes, and lions—beneath the wooden rafters and overlooking this art-filled place he called ‘home.’

“I don’t know if I’m called a constructivist, sculptor, or painter…But I wouldn’t mind being called a backwoodsman.”

– Bernard Langlais, 1961

Early Life

Bernard Langlais was the oldest of ten children born to a self-employed carpenter and a homemaker. He grew up on Treat-Webster Island (also known as French Island) in Old Town, Maine, a logging community comprising several islands in the Penobscot River near Orono. His mother was a first-generation French-Canadian; French and English were spoken in their home.

After high school, Langlais left Maine to study commercial design in Washington, DC. He paused his training to enlist in the Naval Air Transport Service during World War II. Following his discharge, Langlais gravitated toward fine art. He was inspired by the work of Norwegian artist Edvard Munch and energized by three summers spent at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, an experimental school set on a farm in central Maine. He abandoned commercial design and began painting vibrant, expressionistic landscapes. He continued his training at the Brooklyn Museum School, spent a year in Paris on the GI Bill, and received a Fulbright Scholarship to study in Norway. He married Helen Friend, a fellow Mainer, in Oslo in 1955. They later settled into a loft in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood.

Painting occupied Langlais throughout the 1950s, although he never settled on a single style. He moved restlessly from naturalism toward abstraction, from traditional landscapes and still lifes to experiments inspired by the European avant-garde. He was most prolific in Norway and during summers at the rustic cottage he and Helen purchased on the St. George River in Cushing, Maine. He became increasingly drawn to the climate, terrain, and ethos of his home state, while also growing dissatisfied with the painting medium. “The alien materials of bristle, pigment, and canvas were frustrating and without life,” he said.

New York & Maine

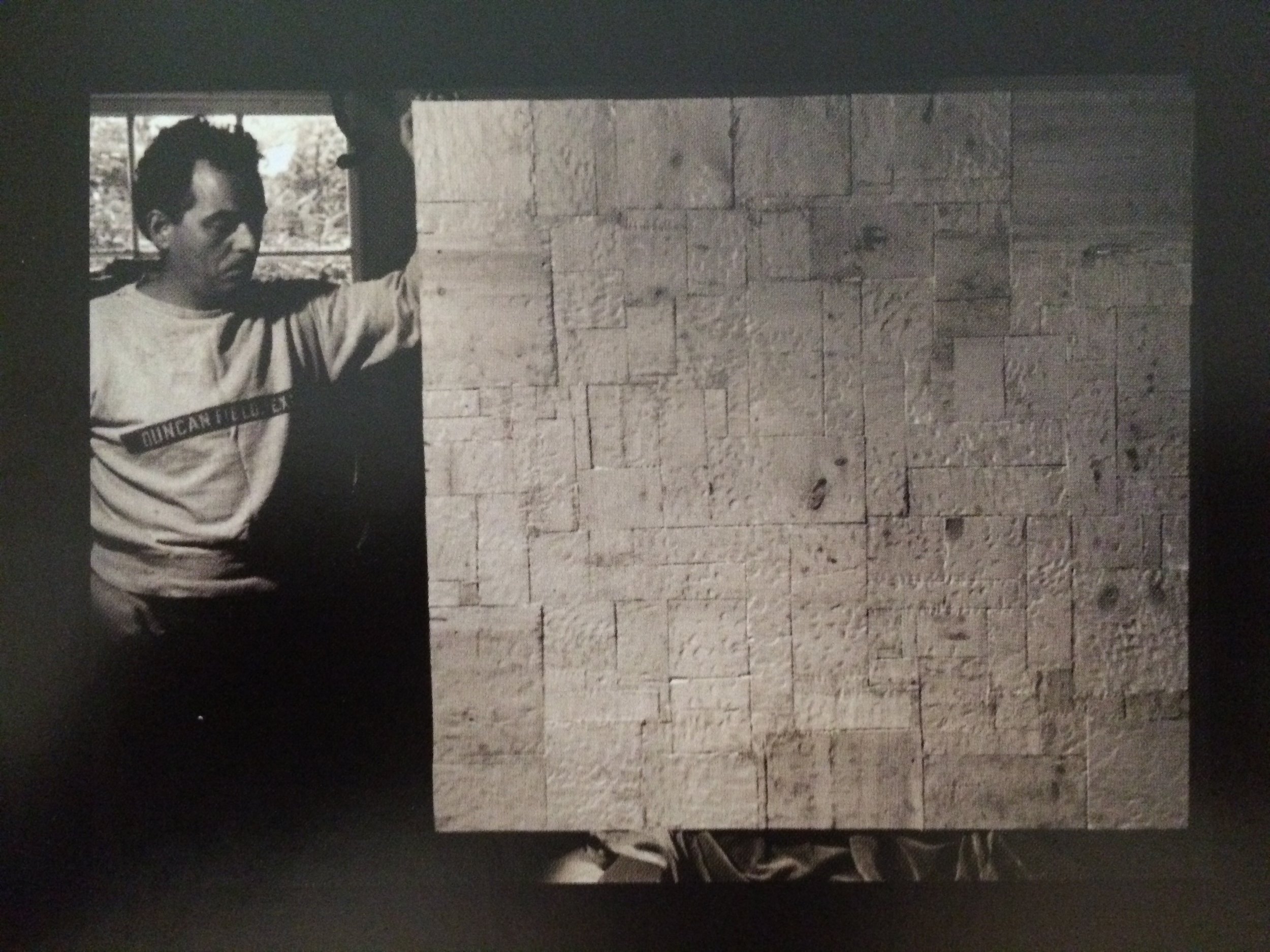

Photo: Rudy Burckhardt

During his first summer in Cushing, Langlais constructed a mosaic-like wall for his cottage from a pile of wood scraps. Energized by this home carpentry project, he brought the idea back to New York. He acquired a supply of odd pieces of wood and manipulated and assembled them to create distinct, abstract compositions, which he called “wood paintings.” These works aligned him with a group of artists who were finding expressive validity in materials not then considered appropriate to fine art. He was included in two genre-defining exhibitions—New Forms—New Media at the Martha Jackson Gallery in 1960 and The Art of Assemblage at the Museum of Modern Art in 1961—and was the subject of a one-man show at the prestigious Leo Castelli Gallery.

“With the wood, I can express my personality and feel in my environment.”

– Bernard Langlais, 1961

Langlais began to explore figurative subjects in wood in the early 1960s—in particular, the animal life of coastal Maine. Many from the audience that revered his first wood paintings criticized the new work, calling it “primitive,” “craftsman-like,” and appropriate for a gift shop. The stress of being in the limelight, and of having his work publicly scrutinized, took its toll on the thirty-something artist. Langlais grew disillusioned with the competitive New York art scene—the sterile, confined gallery spaces and unspoken rules of engagement.

Summers is Cushing were an escape from the social and psychological pressures of New York. They also allowed him space to work on a larger scale, and unlimited access to the material that most energized his creativity.

“The Farm”

Banner Image and this Photo: David Hiser

The Langlaises purchased the farm across the road from their summer cottage in 1966 and began to live year-round in Cushing. Bernard promptly made a monumental gesture about his sense of place, building a literal “gift horse” for Cushing: a thirteen-foot-tall wooden horse on a rocky outcropping of his land. Requests for several major commissions followed, including a seventy-foot-tall Indian for the Town of Skowhegan, Maine, his most widely publicized work.

“It’s a kind of music, this country. I want to use it the way a farmer uses it to pasture his cows, horses, sheep.”

– Bernard Langlais, 1975

Farm chores, muddy ponds, and changeable weather became as integral to Langlais’s art as they were realities of his environment. He constructed larger-than-life works in wood, and placed them in pastures, ponds, on barn walls, and in the company of his growing cadre of farm pets. Defying the static, climate-controlled art gallery, he created an evolving outdoor exhibition rooted in place. He welcomed nature as a contributor to the artworks, and he welcomed curious visitors to wander among them. He sourced materials and equipment from neighbors, adapted his work to the seasons, and chose subjects that were often local in theme or intended audience. At the time of Langlais’s death in 1977, his outdoor art environment comprised well over one hundred wood reliefs and three-dimensional pieces, including more than sixty-five monumental sculptures.